How Labour could win without Starmer

It won’t be easy. The attempt might fail. How could the party maximise its chances of success?

Perhaps all will now be well. Maybe voters will come round to backing this week’s Budget, liking Rachel Reeves’s plans to revive the economy and resuming their optimism about Britain’s future.

But what if they don’t? What if her poll ratings and Keir Starmer’s remain toxic, with Labour lagging far behind Reform and struggling to attract even 20 per cent support? Unsourced media stories talk of plans to challenge Starmer. Would a change of leader do Labour any good?

In a recent column for The Times, Fraser Nelson put the case against replacing a prime minister between elections. He argued that Downing Street’s new tenant would lack their own mandate:

“Without this, cabinet rifts become harder to control; backbenchers harder to tame. Things start to fall apart. Usually, such leaders end up calling an election either to seek a personal mandate (Theresa May) or put the party out of its agony (Sunak). Or just because he can no longer control parliament (James Callaghan).”

Nelson’s list is telling but incomplete.

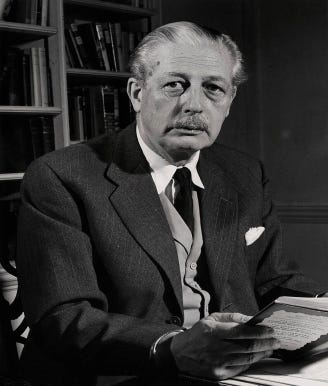

In January 1957, Harold Macmillan succeeded Anthony Eden. Two months earlier Britain had been humiliated by its disastrous, failed conspiracy with France and Israel to wrest control of the Suez Canal from Egypt. A recurring illness compounded Eden’s problems. He resigned when his doctors warned that he might not survive if he stayed in office.

Macmillan had a rocky start. Polls and by-elections initially told a story of continuing Conservative unpopularity. But gradually his fortunes started to improve. With rising living standards, Macmillan was able to promise:

“You will see a state of prosperity such as we have never had in my lifetime – nor indeed in the history of this country. Indeed let us be frank about it - most of our people have never had it so good.”

In October 1959, he led his party to a third successive victory, with an increased majority.

A more immediate transformation of Tory fortunes took place when Margaret Thatcher was deposed in November 1990. Conservative support stood at 34 per cent, eight points down since the 1987 general election. (For comparison, Labour is currently 16 points down on last year’s election at 19 per cent.) In 1990 just 25 per cent told Mori (now Ipsos) they were satisfied with Thatcher’s performance as prime minister; Ipsos’s pre-Budget survey found that 13 per cent are satisfied with Starmer.

Within weeks of succeeding Thatcher, John Major’s satisfaction score was 61 per cent. The Conservatives’ poll rating had recovered to 45 per cent. In 1992, the party won its fourth general election victory, with more than 14 million votes – a record that still stands.

(Soon afterwards, on Black Wednesday, it all went pear-shaped, when Britain crashed out of Europe’s exchange rate mechanism. But that’s another story. The fact remains that in 1990 the Tories forced out an unpopular prime minister and went on to win the next election.)

Now to 2019. That May, following the Brexit party’s success in the elections to the European Parliament, Tory support was around 20 per cent; just 25 per cent were satisfied with Theresa May’s premiership. Following her resignation, Boris Johnson did not have the same immediate effect as Major in 1990, but his satisfaction score was higher than May’s, peaking at 46 per cent in October. And, of course, in December he led the Tories to victory with an 80-seat majority, its biggest since 1987.

That history suggests four lessons for a new Labour leader if the party decides it needs to replace Starmer.

First, talk up the scale of the change. Eden remained popular with voters following the Suez disaster. The severity of his illness was largely hidden from public view. But at Westminster and in Whitehall, Britain’s humiliation was clear, as was Eden’s inability to handle it. Macmillan brought stability and began the process of adjusting to Britain’s post-imperial destiny.

Major and Johnson were more obviously agents of change. In 1990, Thatcher’s increasingly strident and confrontational style was alienating more and more voters. They hated the poll tax. Pro-European Tory MPs (in those days there were lots of them) were appalled by her hostility to Brussels. Major was more conciliatory in style, and constructive towards the EU. He scrapped the poll tax. He appointed Michael Hesetline, Thatcher’s nemesis, as his deputy. Votes wanted a change of government; Major provided it.

Johnson’s big change was to clear up the Brexit mess, which had largely been created by MPs like him preventing May from implementing her plan for life outside the EU. (A brief reminder: she sought what today’s pro-Europeans want Labour to negotiate: a trade deal with many of the characteristics of the Customs Union and Single Market.)

By taking a harder line, Johnson marginalised the Brexit Party and fought a successful election campaign with the slogan, Get Brexit Done. We all know the sequel: the damage done to Britain’s economy and the disintegration of Johnson’s reputation – or, perhaps more accurately, the discovery by the electorate of deep character flaws that political insiders and long known, but whose warnings had been largely ignored.

So, the most important lesson for a new Labour leader: be a change prime minister, not a guardian of continuity.

Secondly, the change must be more than a fresh rhetorical style. In keeping with his previous career, Eden was a foreign policy prime minister. He was brought down by his utter failure to apply what should have been his greatest strength to a changed world. In contrast, Macmillan approached the 1959 election by concentrating on the home front and rising living standards.

Major and Johnson offered more obvious policy contrasts with their predecessors. What could a successor to Starmer offer that has the same impact as scrapping the poll tax or sorting out Brexit? This is not just a matter of getting the policy right. It goes to the heart of the new leader’s need for a compelling narrative – a fresh account of the kind of Britain they want and how they plan to get there.

Third, Macmillan, Major and Johnson restored control over their party. Major’s approach was the most conciliatory of the three, Johnson the most brutal. His destruction of the Tory’s pro-European wing has had lasting consequences that have contributed to the party’s current plight. But in 2019, his exam question was how to win the next election. He passed.

Fourth, economics played a big role in the three successes. Only Macmillan could tell a story of rising living standards; but Major and Johnson offered policies that promised a more prosperous future. For Major it was membership of Europe’s exchange rate mechanism, for Johnson Brexit. One of the quirks of history is that the Tories won both elections by making opposite mistakes: getting too close to Europe in 1992 and moving too far away in 2019.

Whether Starmer should be replaced is a question for another day and another post. But others far closer to the battlefield have started to ask it. They may do so more intensely when the Budget dust settles. It makes sense for them to consider the consequences of changing leader and how to prevent Labour’s present crisis from going to waste.

Even if Labour managed to replace Starmer without becoming even more unpopular, even if it were possible (as you demonstrated in your last Substack) for tactical voting to defeat Reform in 2029, there remain enormous risks for Labour to win again under FPTP.

Surely Labour should be urgently considering the preference of a majority of Labour voters, members, CLPs and unions for Proportional Representation to replace FPTP.

Or is Labour's reluctance to consider power-sharing -- in a coalition government with LibDems and Greens -- to be responsible for a 2029 landslide victory for Reform under FPTP?

Previous local attempts at forming "progressive alliances" between parties, to encourage tactical voting, have seen Labour expel any member caught collaborating for the greater good.

Even in the era of personality politics the necessary point of any change in leadership would be a change in direction, in policies. I don’t see that anywhere just now.

A move away from FPTP is necessary, and could make up part of either a refreshed direction under the current leader, or an alternative package. In the era of populism and awful media, we can’t afford majority government elected by minority vote. It’s too risky. The probable impact of a wider set of views in parliament and a need for “messy” collaboration in government has strengths as well as weaknesses.

Stop the media led focus on personalities and let’s change the system - a big change that should be sold as strengthening democracy and uk governance