Let us face the future... again

A modest proposal for improving Labour's fortunes after a rocky start

Here is a programme for Government that Keir Starmer, Rachel Reeves and their colleagues might consider.

Ensure a job for everyone who is able to work

Reduce taxes on income, increase them on property

Abolish poverty with a minimum income for all

Replace all bad housing with new homes providing healthy, cheerful living conditions for all

Revamp all the old industrial towns that have declined in recent decades

Set out a plan to improve diet and tackle obesity

Build centres for music, drama and art in every community

To be sure, that list is incomplete. It does not address climate change, or the impact of social media, or what to do about AI. But I suspect the Chancellor’s main quibble would be that it takes no account of Britain’s parlous finances. She tells us that this is a time to take tough decisions and blame the Tories; expensive dreams must wait until our national finances allow.

Well, yes, every policy must be paid for. But does that mean we can’t dream of the future we want to build? The question is worth asking because the list above is not new. It repeats proposals set out when Britain was in a far more parlous state than we’re in today.

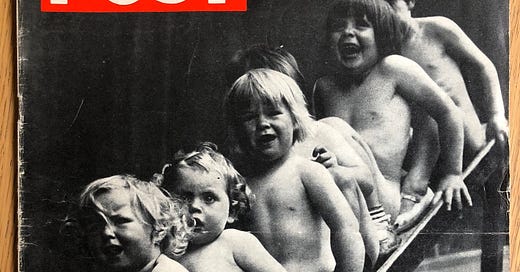

At the start of 1941, Britain stood alone. Our cities were battered by the Blitz. Life was drab and difficult. Food was severely rationed, clothes hard to come by. On January 4, the popular weekly magazine, Picture Post, put all that to one side. Instead of pictures of tanks, generals, political leaders or wrecked city centres, its cover showed six small children playing happily on a slide. Underneath was the caption: A Plan for Britain.

The whole issue was devoted to what should be done after the war. In its foreword, it recalled how “an idea of the country we wanted to make” was missing at the end of the First World War. “The plan was not there. We got no new Britain, and we got no new Europe. This time we can be better prepared. But we can only be better prepared if we think now. This is not a time for putting off thinking, ‘till we see how things are.’ … Our plan for a new Britain is not something outside the war, or something after the war. It is an essential part of our war aims. It is, indeed, our most positive war aim.”

If ever journalism captured the public mood, that issue of Picture Post did so magnificently. As the war went on, voters’ demands for a different post-war Britain grew louder and more insistent. In 1942, the Beveridge Report laid out the principles of national insurance, welfare reform and a new National Health Service. The 1944 Education Act overhauled our school system. Labour’s 1945 manifesto, “Let us Face the Future”, promised to implement these reforms, and also to “proceed with a housing programme with the maximum practical speed until every family in this island has a good standard of accommodation.”

These were all great ambitions – and Picture Post got there first. (In the list at the start of this blog, I omitted Picture Post’s call for an NHS, national insurance for all, child benefits, and a reform of the school system, because the Attlee government did them all.)

It did not get everything right. Nor did Attlee’s government. By today’s standards Picture Post veered too far towards state control and public ownership. It said little about innovation, private investment or the challenges and potential of new technologies such as television. But it was published almost 84 years ago. What is striking is not its mistakes but its continuing relevance. Picture Post’s passion for a better, fairer society still resonates.

Why, then, did it strike so much more of a chord in far tougher times than today’s Government has managed to do, three months after its landslide victory?

To approach an answer, let me offer four differences between Picture Post and Rachel Reeves.

First, Picture Post acknowledged its inheritance – a national failure to sort things out after the First World War – but did not dwell on it. It used its descriptions of what was wrong as a springboard to discuss the future, not to drag every point back into a sour finger-pointing blame game. Its readers wanted a vision of how to make things better. By banging on so persistently about Tory failures and black holes, Reeves distracts voters from her hopes for the future.

Second, Picture Post used compelling language, together with vivid pictures and graphics, to make its case. Each section had a summary box listing “What we want”. It related everything it advocated to people’s families, homes and communities; their hours at work and their time at home. Readers could see clearly how their own lives could change.

This year, the power of Labour’s five missions are let down by impersonal language that is used at seminars, not the school gate: “Highest sustained growth in the G7”, “clean energy superpower”, “NHS fit for the future”, “barriers to opportunity” and so on.

Third, Picture Post made a much better job of discussing the time it would take to reach its goals.

As it happens, we can make a precise comparison. In his speech to Labour’s conference last year, Starmer said: “The age of insecurity is loaded onto the backs of working people. But there’s no magic wand here. A decade of national renewal. That’s what it will take.”

Picture Post depicted the same timescale as less of a slog and more of an adventure: “This new and better Britain could, we believe, be realised – given goodwill – within ten years. Not in the time of our great grandchildren, but before we have been worn out; before many of our children are grown up”.

Fourth, and most important, Picture Post conveyed a confidence that big changes were perfectly possible. The magazine had impact not because it was informed by a grand ideological design but precisely because it wasn’t.

The good news for Labour after the last few difficult weeks is that Starmer and Reeves belong to the same tradition of practical reform. Their ambitions remain intact. But they do not convey either the belief or the excitement that Picture Post generated during the worst days of the blitz.

Here’s some free advice for Reeves as she prepares to deliver next week’s Budget speech. We’ve got the point about tough choices. We see the clouds; now show us sunshine. Talk not about what the Tories didn’t do and you can’t, but what you can do – and how it will transform our daily lives. In Britain’s darkest hour, Picture Post lifted its readers’ spirits. Time for you to lift ours.

Spot on. A voice calling for Starmer & Reeves to project a sense of movement towards rather than away from. Let us hope they will listen and offer hope rather than adenoidal miserabilism.