Reform's winning post is closer than I thought

Revealed: the brutal arithmetic that will shape the next general election

It’s worse than I thought. I am not referring to Labour’s troubles over the benefits system. Other people have written copiously about that. Instead, here is fresh information that could have a more lasting impact on British politics.

Last week I suggested that for Nigel Farage to become prime minister, Reform’s percentage share of the vote would need to be “somewhere in the mid 30s”.

I was wrong. Reform’s target is less than that. It could be below 30 per cent.

For we number-crunchers, our trickiest task between now and the next election to convert the voting percentages reported by the polls into the numbers of MPs each party would have in the House of Commons. This is now harder than ever. Our first-past-the-post voting system can do funny things when so many parties are competing for our support.

Large-sample MRP surveys deal with this by applying detailed demographic and political polling data to each constituency. They are the best available guide to our new political landscape – but they varied wildly at last year’s election. One of the most accurate was YouGov.

Last week, YouGov published its first MRP survey of the current parliament. Plainly, like any poll four years out from the next election, it tells us next to nothing about who will win next time. Its value is that, once again, it reveals the structure of the relationship between votes and seats. From this we can estimate how many MPs each party might have on a range of scenarios. It is this exercise that shows how Nigel Farage could become prime minister even if more than 70 per cent of voters reject Reform.

It also shows that Labour’s prospects depend not just on how many votes it wins, but on the battle on the right between the Conservatives and Reform.

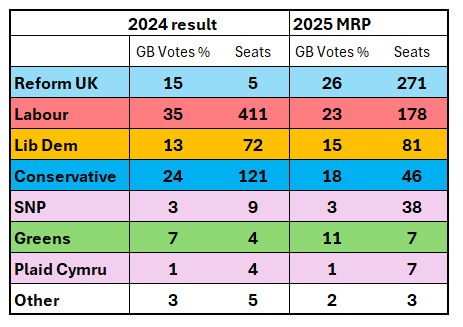

Let’s start with YouGov’s central MRP projection:

The first thing to note is that Reform would have far more MPs than any other party – with only 26 per cent of the vote. Most polls put them higher than that. However, 326 MPs are needed for an overall majority. If Reform joined forces with the Tories, the total would rise to 317. This is the same as the Tories won in 2017. Theresa May carried on with the help of ten Democratic Unionists from Northern Ireland. Last year the DUP contingent was down to six. If the next election were to work out exactly as YouGov’s figures suggest, it is hard to see a stable government being formed, whether led from the right or left.

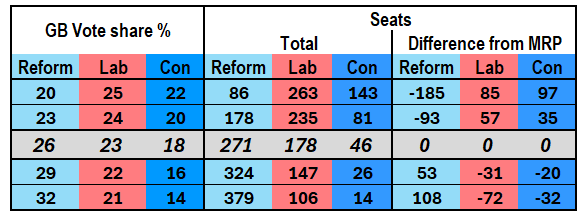

Next, here are possible scenarios for what could happen if Reform did better, or worse, than in YouGov’s survey. From now on the figures are my responsibility, not YouGov’s. I start with their seat-by-seat projections and make my own adjustments. I assume first that for every three votes that Reform gains (or loses), two come from (or go to) the Tories and one from (or to) Labour. This fits the pattern of Reform’s rise since last year. Secondly, I assume that the same variations apply to every seat. Thirdly, I leave support for the other parties unchanged.

There are of course limitless ways to adjust the figures. New tactical voting could affect the outcome. The Lib Dems, Greens and SNP may end up in a different place from where they are today. And each estimate is subject to a margin of error. However, in the scenarios that follow, I doubt that any of these factors would change who governs Britain .

The table below shows my estimates for the number of seats that would be won by each party on four alternative scenarios: Reform a) up three percentage points; b) up six; c) down three; d) down six. (I have not shown the figures for the other parties, as in these scenarios they do not vary significantly from YouGov’s projection.)

The figures are dramatic. With 29 per cent support, Reform’s 324 MPs would put it on the edge of an overall majority. Indeed, if Sinn Fein again have seven MPs, none of whom take their seats, there would be 319 MPs from all other parties. Reform would have a majority of five. In reality, allowing for a margin of error in the final totals, if Reform wins 29 per cent of the votes, Farage becomes prime minister. The only doubt is whether he leads a minority or majority government.

Add another three percentage points to Reform’s total, then a 32 per cent share of the vote would give it 379 seats, and a comfortable majority even allowing again for a margin of error.

On the other hand, Reform would suffer greatly if its support falls. On 23 per cent, it would no longer be the largest party, and on 20 per cent it slips to third place – possibly fourth if it wins slightly fewer seats, and the Lib Dems slightly more, than in my projection. On the morning after the next general election, Reform with be either blessing or cursing impact of first-past-the-post for its result.

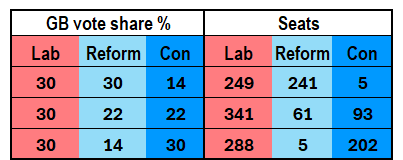

Just one more bit of number-crunching to come. Let us suppose that Labour regains most of the support it has lost to progressives over the past year and wins 30 per cent of the vote, leaving Reform and the Conservative with 44 per cent between them. It makes a huge difference how that 44 per cent is divided.

Here are three Illustrations: Reform dominating the right-of-centre vote, Conservatives dominating it; both parties level.

The lesson is clear. Labour badly needs Reform and the Conservatives to battle to a draw. Then 30 per cent gives Labour outright victory. But if either Reform or the Tories crumble, 30 per cent could leave Labour well short. This should not be a surprise. The party owes its landslide victory last year to the split in the right-of-centre vote. Labour won 144 seats with fewer votes than the combined Tory and Reform total.

Enough of numbers. What of the politics that flow from them? The task for both Reform and the Tories is clear: they need to knock the other out. The challenge for Labour is more complex. There is little it can do to keep both the Tories and Reform alive except, perhaps, concentrate its attacks on the stronger party if its weaker rival seems to be drifting towards death’s door. Beyond that it must win back voters from both its flanks: disappointed progressives and those voters who used to vote Labour but moved to the Tories in 2019 and have since moved on to Reform.

To state the obvious, Labour has four years to recover. It can then campaign on its record and put its current troubles behind it.

However, while a week can be a long time in politics when it is played out as a drama, even four years can be a short time when trying to turn round a country in trouble. On welfare, immigration and Europe, Labour’s record in 2029 will be determined by decisions Starmer takes this year. As for the latest controversy, over Morgan Mc Sweeney, Starmer’s chief of staff, the fate of individual staff members in Downing Street matters only to the extent that it affects those decisions.

One final point. Starmer now regrets saying Britain risks becoming an “island of strangers”. When he said it, he was unaware that in 1968 Enoch Powell was lauded by anti-immigrant voters for predicting that British people would be made to feel “strangers in their own country”. It’s a comparison that can do Labour no good. If its stance is that Reform raises legitimate concerns but goes too far, not only will this alienate the progressive voters it needs to win back; it will also fail to impress those target voters currently supporting Reform. A choice of full-fat Farage with semi-skimmed Starner is one that the prime minister is wise to avoid.

Labour really ought to open their eyes. Electoral reform would be the best way to allow people to vote for who they really wanted. FPTP leads to tactical voting to keep people out.

I don't think that Starmer is evil incarnate, as those on the hard Left do, but he is unimaginative, and I don't think can really deal with the threat from the hard Right, which would mean bringing in European-style PR systems.