To stop Reform, change the voting system

Without change, Farage could become prime minister even though most voters can't stand him

When those at the top of Reform change their mind, we should take note. When their reason is to defy the will of the electorate, we should take action.

Last year Reform advocated proportional representation for elections to parliament. It complained that “new parties are shut out of the political system” and promised a referendum to change it. After the election, when Reform won half a million more votes than the Liberal Democrats, but 67 fewer seats, its complaints grew louder.

Now their tune has changed. Following last month’s local elections, the Spectator’s Steerpike columnist asked Richard Tice, Reform’s deputy leader, whether the manifesto commitment still held. Tice replied.

“Look, I love the PR system. I mean, obviously there’s a number of different PR systems... But ultimately for parliamentary elections, we’ve got first past the post and our job is to win with it. So that’s the bottom line and I don’t see that changing anytime soon.”

Not quite a screeching hand-brake turn, then, more a gentle prelude to a Reform government discovering the virtues of first past the post.

No wonder: having been screwed by FPTP last year, Reform were its beneficiaries last month, when a national vote share of just 32 per cent gave them 39 per cent of council seats and outright control of ten counties. They have every reason to dream of winning a parliamentary majority at the next election if they can push their vote up just a bit more. An Ipsos poll over the weekend projected just such an outcome. After all, Labour achieved a landslide victory last year with barely one-third of the national vote.

In a way, this is just the latest version of an old argument: our voting system is prone to big distortions. Advocates of change have been banging their heads against a variety of brick walls for decades. I first wrote about electoral reform more than 40 years ago. Should we not just shrug our shoulders and accept that yet again the status quo and all its distortions will prevail?

Here are two reasons why this time is different. The first is that the distorting effect of FPTP was greater last year than ever before, It wasn’t just the contrast between Reform (4.1m votes, 5 MPs) and the Lib Dems (3.5m votes, 72 seats). It was also the contrast between Labour’s vote share (the lowest ever for a party securing a parliamentary majority) and seats won (the third highest for any party since the Second World War). Together these two things gave Labour the biggest “winner’s bonus” in British history:

Before last year, the biggest post-war bonus was the 144 achieved by Labour in 2001.

This, then, is the arithmetic case for saying that change is overdue. To the underlying biases of FPTP we must now add the impact of party fragmentation. For the first time in more than a century, four competing parties all won more than ten per cent of the vote. This has led to changes in the winning post. In 57 seats that Labour gained, its victorious candidate last year won fewer votes than its defeated candidate in 2019. Forty-two of its MPs were elected with less than 35 per cent of the vote.

That gives us one reason for changing the voting system. But there is a second, and arguably more important, reason. It is that the political case for change is greater and more urgent than in the past. Until now, FPTP has done less damage than reformers claimed. Today, the prospect of a democratic disaster is real.

Again, let’s start with what happened last year. Yes, the gulf between Labour’s votes and seats was preposterous. But voters overwhelmingly wanted to boot the Tories out; and the evidence from polls and tactical voting analysis is that most voters were relieved, if not always ecstatic, that Keir Starmer became prime minister.

We can go further. In the post-war era, with the same two parties occupying the two top places in every election, there has been no election when the rightful winner has been denied its prize and Britain has been lumbered with the “wrong” government. We can argue the toss about some contests but even with the two most commonly-cited elections, 1951 and 1983, I would argue that Britain ended up with the “right” government. My reasons are set out in the footnote to this post.

This democratic virtue of FPTP would not apply to a Reform-led government. It is currently not just Britain’s most popular party but its most hated. YouGov regularly asks people how likely they are to vote for different parties, on a scale from 0 (“would never consider voting for them”) to 10 “would definitely consider voting for them”). The results are clear.

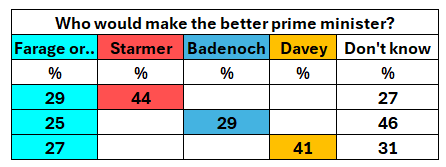

Polls that ask who would make the best prime minister show Starmer and Farage vying for first place, with Badenoch consistently a distant third. YouGov recently tested the issue in a different way: asking people who would be best when offered a series of two-way choices, pitching each of the four main party leaders against each of the others. These are the figures for the contests involving Farage:

Starmer and Ed Davey beat Farage comfortably. Farage loses each time, even to Badenoch. For completeness the remaining contests show Starmer beating both Badenoch (36-25%) and Davey (27-25%), while the least probable contest has Davey beating Badenoch by 33-21%. So, despite Reform leading Labour by a comfortable margin, Starmer is the overall winner and Farage the clear loser when people are asked who they want running the country.

In short, should Reform win enough votes to make Farage prime minister – in percentage terms that probably means somewhere around the mid 30s – then, unlike last year and for the first time in living memory, the country is likely to have a government that most people really don’t want.

It’s perfectly possible that we shall be spared this nightmare. Reform’s vote may well slip. Once again in will be punished by FPTP rather than win enough votes to benefit from it. But as long as Reform maintains the support of 30-plus per cent of voters, then election after election, we could end up with a government that, for the first time in modern British history, a clear majority of voters actively rejects.

The only way to avert that risk is to change our voting system. In a future post I shall discuss the options.

Footnote

In 1951, the Conservatives returned to power despite winning fewer votes than Labour. There are two reasons why this is not as anti-democratic as it seems. First, four Conservative (more precisely Unionist) candidates in Northern Ireland were unopposed. Had these seats been contested, around 160,000 votes would have been added to the party’s national total.

Secondly, the Liberals were far closer to the Tories than to Labour. The Conservatives stood aside in eight mainland seats, in favour of the Liberals in seven and an independent in one. Indeed, on October 15, ten days before the election, Winston Churchill travelled to Huddersfield to speak in favour of an old friend, Violet Bonham Carter, the Liberal candidate for Colne Valley. Churchill said he was doing this because Britain’s “progress as a nation depends upon the defeat of the socialist government... The more spirit which has prevailed here spreads, the fewer Liberal votes throughout the country will be wasted and the more surely a coherent and decisive verdict of the electors will be obtained against socialism”.

Given a) that Labour’s lead over the Tories was 230,000; b) that this would have been reduced to 70,000 had there been contests in every seat in Northern Ireland; and c) that the Liberals won 730,000 votes nationally, the election of a Tory government was a statistical curiosity but not a scandal. (Bonham Carter herself lost by just over 2,000 votes but six Liberals were elected, five of them in seats where the Tories stood aside,)

In 1983, Margaret Thatcher won her biggest victory, a majority of 144. But the 13 million votes won by the Conservatives were outnumbered by the 16.3 million votes won by Labour (8.5 million) and the Liberal-Social Democrat Alliance (7.8 million). Thus, so the argument goes, FPTP deprived voters of the progressive government that most of them wanted.

Not so. The evidence is clear and set out in detail in Appendix 5 of Ivor Crewe and Anthony King’s book, SDP. Issue by issue, views of Social Democrat voters ranged across the ideological spectrum. Overall, they divided fairly evenly between those who tilted to the left and those who tilted to the right. This meant that, among the electorate as a whole, Britain had more right-of-centre than left-of-centre voters The notion that a “progressive majority” was thwarted is a myth.

Hi Peter,

I totally agree the electoral system needs to change in the face of the Reform threat. If the 2 parties that still support electoral reform took strategic actions on where they do and don't stand candidates, I think they could quite easily force electoral reform in this parliament. The Reform threat is surely worth more than the few stand-asides seen in 2019.

https://ewanhoyle.substack.com/publish/posts

The thing is, in the same piece you lay out the compelling case for electoral reform, you also explain precisely why it won't happen. Labour has a "winner's bonus" of 192 MPs, which means that a move to proportional representation would entail 192 turkeys voting for Christmas.