What can possibly go wrong?

A practical guide to the risks that Rachel Reeves is taking with her Budget

Rachel Reeves knows about risk. When she worked at the Bank of England, the Bank published a twice-yearly Financial Stability Review, which assessed the big risks facing the economy and the markets. Today, it is standard practice for companies, charities and public sector bodies to keep a Risk Register – an analysis of things that might go wrong. They judge the probability of each risk upsetting her plans, and the likely impact if it does.

What risks face the Chancellor between now and the next general election, as she seeks to speed up Britain’s growth rate? Here is my subjective version of a financial Risk Register following her Budget.

Government spending on sickness benefits and the NHS rises faster than forecast

Probability: likely

Impact: major

Reeves has tried to reduce this risk by giving the NHS more money to reduce waiting lists, and backing reforms both to modernise the NHS and reverse the trend towards more people who have long-term sickness.

The Chancellor’s plans are ambitious. There is a strong case for tough measures to break free from the failures of past governments on both fronts. But will reform succeed as much and as quickly as Reeves hopes?

The Budget measures lead to higher unemployment

Probability: unlikely

Impact: moderate

When such big decisions about taxes and spending are implemented, some change is almost certain. But overall, what will be the size and direction of this change overall? On the one hand, the rise in employers’ national insurance will hurt the jobs numbers. On the other hand, higher spending on the NHS and infrastructure should generate new jobs. Even harder to predict are the changes in the general environment for investment and consumer spending.

Netting it all out, I expect the overall impact of the Budget on jobs to be broadly neutral. But if unemployment does rise, then lower tax revenues and extra spending on benefits will damage the public finances.

Trade war disrupts the global economy

Probability: moderate (If Trump wins); minor (if Harris wins)

Impact: catastrophic

Donald Trump threatens to impose massive tariffs. These could provoke a global trade war. The consequences would be terrible. But will Trump actually go ahead? At the moment, it is likely but not certain that he will compromise to some extent on what he does. If he wins next week, we shall have a better idea of the probability by the middle of next year.

That is, however, not the only cloud on the horizon. There is continuing uncertainty about the rules governing trade between China and the West. Moreover, Britain’s trading prospects depend to a large extent on whether or not the barriers to trade with the EU are removed, reduced or kept and enforced.

Taxes paid by non-doms, high-paid workers and wealthy investors rise by less than expected

Probability: likely

Impact: moderate

Most people agree with the moral case for requiring those with the broadest shoulders to bear the greatest weight of tax rises. The Treasury accepts that some will leave Britain and/or rejig their finances to keep their taxes down. But what if their forecasts are wrong and tax revenues suffer?

Governments have a particular problem with these kinds of error. Well-run businesses are nimble. If they spot something going wrong, they act quickly to put things right. Fiscal forecasting errors can take a year or more to become clear, and then months more to correct.

Financial markets lose confidence in Reeves and force up interest rates

Probability: unlikely

Impact: major

So far, Reeves seems to have kept the financial markets onside. If her forecasts turn out to be broadly right, or at least maintains the markets’ confidence that she will remain tough if necessary, then interest rates should remain reasonably stable.

I believe that she will take whatever action may be needed, including further tax rises, to keep the markets sweet. Hence the probability verdict of “unlikely”. But I am wrong, then the Truss/Kwarteng episode tells us how big the impact could be.

We have another pandemic on the same scale as Covid

Probability: rare

Impact: catastrophic

This is largely self-evident. The one thing worth adding is that, because of the continuing cost of paying for the pandemic four years ago, the Government would have real trouble responding to another one.

Climate change causes extreme weather conditions and major disruption

Probability: moderate

Impact: moderate

Another insurance-style risk, like Covid. Unfortunately, there is no global insurance system for meeting the cost of such an emergency. But enough is being spent, for example to protect our coasts and river banks, and so reduce the impact?

International crisis leads to sharp rise in energy prices

Probability: moderate

Impact: major

Hopefully the Government has learned the lessons of the crisis precipitated by the Ukraine war. So although the probability is real, given the range of scenarios that could create a crisis (further Russian action, the Middle East in general, and Israel-Iran conflict in particular), the impact is likely to be serious, but less catastrophic than it was two years ago.

Government misses its targets for tackling tax and welfare cheats.

Probability: likely

Impact: minor

All governments promise a crackdown; none meet their targets. However, the targets this time are modest until the later stages of the current Parliament; and even then, any shortfall is likely to be small in the context of the Government’s overall tax revenues.

New rights for unions lead to more strikes

Probability: unlikely

Impact: minor

Few workers these days join unions in the traditional private sector. They are largely confined to national and local government, public services and regulated utilities such as water, energy and transport.

Forty-five years ago, James Callaghan’s Labour government, was brough down by the strikes in the winter of discontent. But times have changed. Even after the relaxation of the laws proposed by Keir Starmer, we shall still be a world away from the Seventies. Reeves will have plenty to worry about in the years ahead. Strikes are unlikely to be one of them.

* * * * *

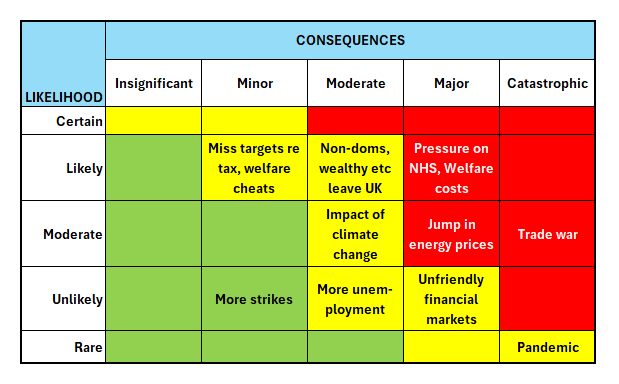

To repeat: these are my judgements. Here is how they would be summarised in a typical Risk Register report, with red for the risks most likely to cause sleepless nights, and green for the least worrying. Readers who disagree with my views should replace them with theirs.

Risk Registers can never be precise or completely objective. No doubt fans of the Government will say I am too bleak – while critics will say I’m not bleak enough.

In fairness to ministers we should add that some things may go better than expected. Items for a “Hope Register” could include

· Buoyant tax revenues that allow higher spending on public services

· A deal with Brussels that smooths trade with the EU

· Stronger growth in the global economy

· Sharp cuts in the price of UK-produced green energy

· Fewer than expected non-doms and wealthy investors leaving the UK

· The crackdown on tax and welfare cheats raises more money than expected

· Increasing approval from the financial markets, allowing lower interest rates and lower debt servicing costs

A much larger issue is whether Labour’s policies will make Britain’s economy grow faster in the long term. The Office of Budget Responsibility thinks they won’t – at least not this side of the next general election. In March, judging Jeremy Hunt’s final Budget, it predicted that our GDP in 2028 would be 8.5 per cent higher than in 2023. Its new forecast for the same five years is 8.2 per cent. In its long-term projection, it expects productivity to rise by 1.5 per cent a year in the mid-2030s – up from 1.2 per cent at the end of the 2020s. It’s something, but unlikely to take the UK to the top of the G7 growth league. The OBR might be wrong – but in which direction?

Bringing this all together, three points stand out.

First, all governments face the same basic problem. Plans never work out precisely as expected. The OBR itself says the public finances could be tens of billions of pounds stronger than forecast – or tens of billions weaker. It estimates that Reeves has a 51 per cent chance of meeting her overall public finance target by 2029.

Exactly 51 per cent? Not 50 or 52? Curious, that. The OBR says this is “based on historic forecast errors”. My rather less precise view of the odds is that Reeves will do well if the hopes that come true offset the risks that blow her plans off course.

Second, both the risks and hopes contain a mixture of policies not working out as forecast (eg welfare reform, non-doms leaving Britain, infrastructure plans) and events outside the Government’s control (such as US trade policy, global energy prices, climate change).

Third, uncertainty is a problem for all governments. Preparing for it is a sign of prudence, not pessimism. Successful organisations work out how to mitigate the risks they face. Labour supporters should hope that the Treasury is one of their number.