A time to moan and a time to choose

To become prime minister, Farage must defy history.

So that’s it. Nigel Farage would become prime minister if an election were held this month. Reform is miles ahead in the polls. More importantly, it would win enough seats either to secure an overall majority or dominate a minority government.

Fortunately for the rest of us, there will not be an election this month. It could well be almost four years away. Past experience tells us that much can change in that time. What more recent experience cautions us is that the arithmetic of elections has changed from the days when two main parties carved up most of the vote and competed for power – days when the relationship of votes to seats, though skewed, was reasonably predictable. We cannot rule out either a collapse in Reform’s prospects – or Nigel Farage becoming prime minister in the teeth of the bitter hostility of most voters.

For progressive voters, the joy of last year’s election result came with a stark warning. If Labour could win a landslide with just 35 per cent support in mainland Britain, might not Reform do just the same next time? Could sauce for Starmer’s goose be sauce for Farage’s gander?

However, there would be one big difference. Last year, voters wanted the Tories out. Keir Starmer was the only plausible alternative to Rishi Sunak. Head-to-head polling showed that voters preferred Starmer by three-to-two. His victory was at best lukewarm, but few people regarded the fact of his arrival in Downing Street as a democratic outrage. Farage enjoys no such lead over Starmer or even Kemi Badenoch today. On current polling numbers a Reform victory would be both very likely and extremely unpopular.

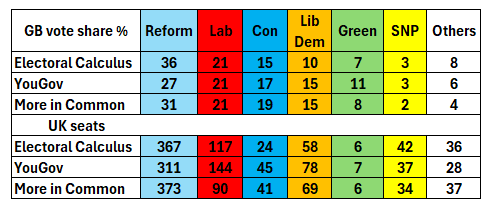

Let’s delve into the data. Three recent large-scale MRP surveys tell a broadly consistent story. With around 30 per cent of the vote across mainland Britain, Reform would be by far the largest party. More in Common and Electoral Calculus show Reform winning an overall majority with a national vote share above 30 per cent, while YouGov, giving Reform 27 per cent support, would leave Farage a little short of the 326 seats he needes for outright victory.

Last year the same three companies’ final MRP predictions all overstated Labour’s performance, by between 19 and 42 seats – but they also overstated Labour’s vote share. That was the main source of error; their MRP algorithms worked fairly well. Their current figures should be taken seriously.

What now? One of the most important lessons from recent MRPs is that many more seats next time will be won and lost small margins. YouGov finds that 82 Reform MPs would have majorities of less than five per cent. A small dip could prevent it becoming the largest party. By the same token, a small rise in its national support would give it a large majority.

More widely, YouGov’s figures indicate an average majority for all parties across all constituencies of just 10 percentage points, well down from the 16 points in last year’s election and 26 points in 2019. It follows that small errors in overall voting intention, or shifts in public sentiment, would cause many more seats to change hands than similar shifts in pre-Reform days.

In short, the recent MRP surveys point to a huge amount of uncertainty about the next election – especially if Reform’s bubble bursts. Today’s polls suggest the joint support of the two main legacy parties[i], Labour and Conservative, is now below 40 per cent, less than half the 84 per cent just eight years ago. We are traversing uncharted territory. But for what it’s worth, history tells us that opposition parties benefitting from government unpopularity have always slipped back significantly from their mid-term peak, typically by around ten percentage points.

The pattern is familiar. Mid-term polls and by-elections allow voters to express their discontent with the government of the day (”send a message” is the cliché). But, to update Ecclesiastes, there is a time to moan and a time to choose. Mid-term polls and by-elections are a time to moan; general elections are a time to choose.

It’s possible of course that Reform will peak well above its current level, and that a ten-point drop from that peak could still allow it to be the largest party in the House of Commons. Even so, it’s clear that it has been gaining ground because of the public perception that the government has failed, especially on immigration and the economy, while the Tories have yet to be forgiven for the state Britain was in when they were voted out of office. This is unquestionably a time of moan and protest. Farage is shrewd enough to know this. Hence his attempt to convert protest votes into positive support, almost weekly presentation of new policies that he says a Reform government would implement.

However, unless he succeeds in persuading voters that he really could run the country, he risks watching his electoral souffle collapse. The current spectacular shenanigans in Kent, where Reform runs the county council, won’t help Farage’s cause. Nationally, the same vote-to-seat gearing that puts him in Downing Street with 30 per cent will punish him if his party gets much less. The chances are that with 25 per cent support, Reform would not be the largest party, and with 20 per cent, not even be the official opposition.

There is one factor that could upset these calculations – in either direction. Last year, tactical voting cost the Conservatives dear, with the Liberal Democrats in particular benefitting. We cannot know how much tactical voting there will be next time, or what its overall impact will be. YouGov’s current data show Labour losing 231 seats to Reform. But in all bar 19 of them, the combined votes of Labour, the Liberal Democrats and Greens exceed Reform’s support. It’s fanciful to image every single progressive voter lining up anywhere behind a single candidate; even so, determined anti-Reform tactical voting could keep Farage out of Downing Street. Likewise, Labour would lose 76 of its current expected 144 seats if all Tory and Reform supporters voted the same way locally. At this stage it’s impossible to predict the size and effect of these rival cross-currents.

Some weeks ago, I argued on Substack that Britain’s voters still divide broadly between left and right in their values. Who governs Britain after the next election could turn on which cluster of tribes, left or right, succeeds more in uniting, seat by seat, to defeat those on the other side of the line.

Meanwhile, if forced to bet on it, I would put my money on Reform slipping back between now and the next election. But if immigration dominates campaigning in 2029, Reform overcomes its teething troubles in the counties it runs, and Labour is still blamed for economic failure, Farage could overcome the hostility of up to two-thirds of voters and still end up as prime minister.

[i] My thanks to Robert Hayward for introducing me to this useful way of describing Labour and the Tories together

This is an updated version of an analysis first published by New World

I’m currently reduced to consoling myself that Reform are the team that went 2-0 up too early in the game. 🫣

The largest group of electors in 2024 is unmentioned as a factor in the analysis and predictions. Turnout nationally was 59.7%: 40.3% of people who had the right to vote decided not to bother. Labour's 33.7% of the national vote meant that it gained the support of only 19.8% of the electorate – but that gave it 63% of Commons seats. The choices of the 2 in 5 abstainers will be more important in detemining the shift between the parties in the next election than changes of mind as to which party voters support. The case for reform of the system by which we elect the national parliament, if democracy has as one of its aims both representation of national views and a degree of consensus, is undisputable, and urgent.