Friday evening update.

My analysis this morning, below, was too cautious. Reform has done even better than I expected, and Labour and the Conservatives even worse.

With most results now declared, Reform will end up with almost half of all county council seats on less than one-third of the vote. According to the BBC, yesterday’s votes convert into projected national shares of Reform 30 per cent, Labour 20, Liberal Democrats 17. the Conservatives 15 and Greens 11.

As I predicted, Reform have eased their way past the tipping point at which our First-Past-The-Post voting system stops punishing insurgent parties and starts rewarding them. But the margin by which it exceeded that tipping point was greater than I expected, and so were the rewards in terms of the numbers of seats won and counties they now control.

Labour’s three narrow overnight mayoral victories now look more like aberrations than a prelude to council seat gains today. Labour did badly in 2021, and hoped to build on their performance four years ago. Instead, they have lost more than two-thirds of the seats they were defending.

As for the Tories, yesterday was an unmitigated disaster. Although they gained one mayoralty (in Cambridgshire) they have also lost more than two-thirds of their seats, and all the counties they controlled. Their projected national vote is fully ten points below their worst performance in the four decades of BBC estimates (they won 25 per cent in 1995 and 2013, when Conservative governments at Westminster were in trouble.)

The Liberal Democrats and Greens lived up to expectations, both making useful gains. This confirms recent polls which show that they, and not just Reform, have made inroads into Labour’s support.

Overnight analysis

Last week, previewing yesterday’s Runcorn & Helsby by-election, I suggested a political version of the Micawber principle: victory by 50 votes, the result happiness; defeat by 50 votes, result misery. OK, Reform’s Sarah Pochin won by just six votes. But the principle holds; and by the same token Labour can celebrate three narrow mayoral victories overnight. However, Labour’s vote fell alarmingly in each of the mayoral contests; and early indications from county council contests confirm the pattern. Labour should not seek to comfort itself by claiming “it could have been worse”.

Reform are, of course, the night’s big winners. By the end of today, it looks likely that gains by the Liberal Democrats and Greens in their target areas will show that it is not just Reform that is benefitting from the decline in the old two-party duopoly – last year’s collapse in Conservative support, compounded by this year’s haemorrhage of Labour votes.

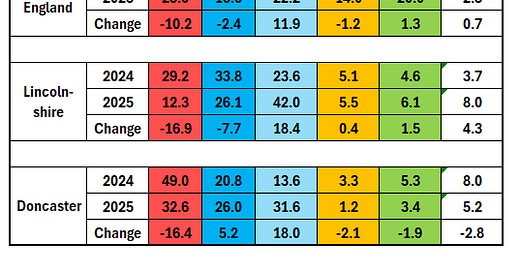

The table below summarises the main overnight results. It compares the share of votes won by each party yesterday with the results from last year’s general election, applying the figures from the relevant constituencies are added together.

As the figures show, Labour suffered double-digit declines everywhere. Their three victories, in North Tyneside, the West of England and Doncaster, were achieved with alarmingly low support: 30, 25 and 33 per cent respectively. These are not kinds of figures that have normally led to victories in the past. Coming from nowhere, Reform won Greater Lincolnshire as well as the Runcorn by-election, and ran Labour close in the other three mayoral contests. It is an astonishing performance, likely to be confirmed by the county council results later today.

What now? In the past, third-party eruptions between general elections have subsided. In the end, for more than a century, the Labour-Conservative domination has returned whenever voters have decided who they want to govern Britain. Maybe the same will happen again. But as well as the long-term social and economic trends chipping away at the old class-based party loyalties, there is a technical reason why we may be witnessing a transformation in our politics.

It's to do with the way our First-Past-The-Post (FPTP) voting system works. It rewards a) large national parties (traditionally L:abour and Conservative), b) parties with specific geographical roots (notably the SNP in their good years) and c) minority parties that successfully target particular seats (as the Liberal Democrats did last year). It punishes medium-sized parties with the kind of broad support that amasses millions of votes nationally, but not enough in particular seats to have many MPs. This used to be the curse that afflicted the old Liberal party and more recently the Lib Dems. Last year it was Reform that suffered, winning half a million more votes than the Lib Dems but 67 fewer seats.

When it was just the Lib Dems trying to break the Labour-Tory duopoly, a rough rule of thumb was that they, and their predecessor parties, needed at least 30 per cent to overcome the biases inherent in FPTP. In 1983, the Liberal/SDP Alliance won just 23 seats with 26 per cent of the vote. Labour was narrowly ahead in the national vote, with 28 per cent, but because its support was more concentrated in winnable areas, ended up with 209 seats.

The arithmetic has changed. With the Greens, Lib Dems and Reform all seeking to undermine the old duopoly – and the nationalists in Scotland and Wales – local candidates need fewer votes to be elected. This, indeed, is the common feature of all the overnight results.

What is true locally is true nationally. The tipping point for a party such Reform is no longer 30 per cent. It’s probably around 25 per cent. That is where they stand in the polls. Later today the BBC will publish its estimate of the national vote share from the country council elections. I would not be surprised if Reform ends up with at least 25 per cent and possibly more.

The scattering of overnight council results shows Reform winning half the seats that have declared. We have yet to hear from southern counties where Reform is weaker and the Greens and Lib Dems stronger. But, for the moment, Reform no longer suffers from an FPTP penalty. it looks as if their share of county councillors will end up broadly in line with their overall share of votes. And that transformation of the way votes translate into seats really should terrify both Labour and the Conservatives.

* * * *

PS. A note about Mark Carney’s victory in Canada. Yes, the Conservatives lost a massive lead, Yes, their leader, Pierre Poilievre, lost his own seat.

However, it’s wrong to suggest that Donald Trump caused Conservative support to crash. Here is how loyalties changed between the start of the year and this week’s election:

Conservative: Early January polling average 45 per cent, election result 41 per cent. Change: down 4

Liberal: 22 – 44: up 22

New Democrats: 17 – 6: down 11

Bloc Quebecois: 9 – 6: down 3

People’s Party: 3 – 1: down 2

Greens: 3 – 1: down 2

Most of the Liberals’ gains were at the expense of the other non-Conservative parties, mainly the more left-wing New Democrats. Trump manged to unite the great majority of progressive voters behind a leader who would stand up to him.

Here in Britain, most of the voters who have deserted Labour since last July have switched to the Liberal Democrats, Greens or SNP. Can Keir Starmer win back these discontented progressives by demonising Kemi Badenoch or her successor as effect effectively as Carney demonised Trump?

(Of course the other thing that changed in Canada at the start of this year was the resignation of Justin Trudeau, an unpopular Prime Minister who was dragging his party down. Mmm. Perhaps we should not make too much of these national comparisons – at least not until nearer the next election.)

Has the voter ID business cost the Tories votes?

It's certainly remiss of Labour to not reverse the mayoral voting system.

In Doncaster and North Tyneside the Conservatives actually gained in share of the vote. In Runcorn they collapsed. The difference between a Reform win and a Reform defeat (by Labour) seems to be the ability of the Conservative Party to get voters out. The failure to mount a strong campaign in Runcorn may well be seen as the moment at which the party consigned itself to irrelevance.