Parties and their voters are not the same

The total votes for progressive parties usually outnumber votes for the Right. We should beware of how we interpret that

The story so far. Before Christmas, the Compass campaign group published a report, Thin Ice, analysing last year’s election results. It argued that Labour would win more votes if it adopted more progressive policies. It offered polling evidence to support its case. I questioned this evidence, and added my own, in my last post for Substack, which was also published by Prospect. Last week, Compass’s Neal Lawson responded to my arguments.

As well as challenging my polling analysis (readers can check out both our views and make up their own minds), Neal moves the argument on by citing a point made strongly in Thin Ice, which I didn’t cover last time. Once again, I disagree with him. Here goes.

Neal writes:

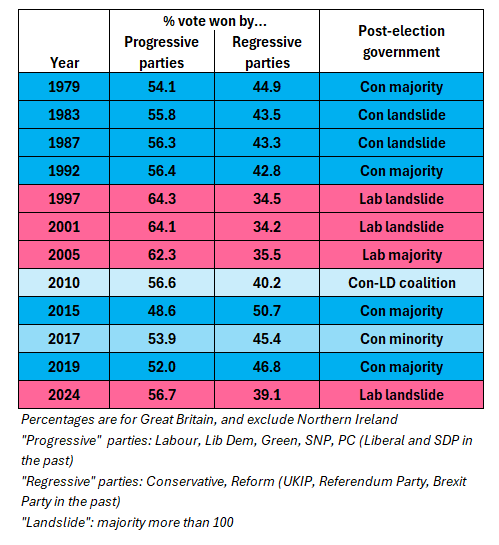

There is a longstanding progressive majority in our country. Parties of the centre and centre-left won more votes than right-wing parties in every election since 1979 bar 2015, but were thwarted by both division and the first-past-the-post (FPTP) voting system, which skews the debate to the right.

He draws on the results of the 12 general elections held since 1979, and compares the total vote share of “progressive” parties with those of “regressive” parties:

As the table shows, the “progressive” total exceeds the “regressive” total in each election except 2015. Yet eight of the 12 elections gave us Conservative Prime Ministers. QED?

Not quite. The assumption underlying Neal’s argument is that those who voted for progressive parties wanted much the same thing, and were thwarted by the way FPTP punished divisions among the anti-Conservative parties.

It is plainly true that FPTP punishes division. Keir Starmer owes the size of his landslide majority to the way Reform divided the right-of-centre vote. But even there, I’m not sure that a right-wing doppelganger of Neal Lawson would have reason to complain. Last year’s divisions on the right owe much to the failures and unpopularity of the Tories. Many Reform voters were as keen as those on the left to boot out Rishi Sunak

To return to Neal’s argument about elections since 1979: two elections stand out: Boris Johnson’s victory in 2019 and Margaret Thatcher’s landslide in 1983.

In 2019, almost exactly the same number of people, just under 14 million, voted Conservative as Labour and the Liberal Democrats together. Add in those who voted SNP, Green or Plaid Cymru – all fiercely anti-Tory parties - and there was a 2.5 million progressive majority (reduced to 1.9m if the Brexit party’s votes are combined with the Tories). Now, it is true that Johnson was not especially popular. But most voters were horrified by the prospect of Jeremy Corbyn becoming Prime Minister. When pollsters asked respondents who would be the better Prime Minister, Johnson led Corbyn by 41-26 per cent.

Moreover, on the central issue of the campaign, most voters sided with Johnson in wanting to “get Brexit done”. According to YouGov, 50 per cent of voters said the negotiated deal with Brussels was good or acceptable, while just 26 per cent opposed it.

In short, voters wanted to get out of the EU and keep out Corbyn. To be sure, a different voting system would have produced a different result. There might have been some kind of coalition. But it’s hard to argue that FPTP gave the wrong answers to the two big questions facing the electorate.

As for 1983, this was the first modern election to make glaringly clear the divisions on the left and centre. Thatcher secured a majority of 144 even though the total vote for Labour (8.5m) and the Liberal/SDP Alliance (7.8m) outnumbered that for the Conservatives (13m) by more than three million.

Here are two problems with progressives saying “we were robbed”. First, the SDP had been created two years earlier because of divisions within the Labour Party. The leaders of the two Alliance parties, David Steel and David Owen, were as hostile to Labour’s 1983 manifesto as to that of the Tories.

Secondly, it’s wrong to say that there was a popular majority for left-of-centre policies. The definitive account of The Birth, Life and Death of the Social Democratic Party, by Ivor Crew and Anthony King*, shows that the views of Alliance voters were closer to Conservative than Labour policies on trade unions, nuclear weapons, Europe’s Common Market, bringing back Grammar Schools and reducing public spending.

Which brings us to the core of the argument. We cannot compare the total votes given to progressive and regressive parties and say that this matches the total number of progressive and regressive voters. The two things overlap but they are not the same. We need to measure opinions separately from votes.

When we do that, a further problem arises. Within each block we must beware of differences. Middle-class Green voters in prosperous towns and villages and working-class Labour voters in struggling red wall constituencies were united last year in wanting to kick out Sunak, but had different views on many other things, from taxation to immigration. Both might be happy be described as “progressive”, but not mean the same thing.

This is an example of a wider truth. Voters make their choices for all sorts of reasons. Which leaders do they trust? Which parties do they hate? Which politicians are competent and honest, which useless liars? Ideology matters hugely to some voters, far less to others. We cannot assume that the outlook of any party is shared by all those who vote for it. An even worse mistake is to assume that the supporters of separate parties are firm allies in a common cause. Which brings us back to the basic point I made the week before last: to determine whether Britain has a progressive majority – at any time and on any issue – we need to measure attitudes, not votes.

I agree with Neal that FPTP should go. It’s hard to defend a system in which Labour wins almost two-thirds of the seats in parliament with barely one-third of the national vote, and for Lib Dems to win fourteen times as many seats as Reform with half a million fewer votes. But the case for changing the system should be made on its own merits, not because FPTP prevents a near-permanent progressive majority with shared objectives getting the government it wants. For all its faults, I don’t believe it does.

* Published by Oxford University Press, 1995. The findings cited here are set out in full on pages 514-6

In simple terms, the progressive/regressive classification is as flawed as the binary choice offered by FPTP.

Voters too often choose flashy performers rather than trustworthy, competent, hard-working leaders

Opponents of FPTP (like me), have to learn to argue for coalition government.